Managing Crises in the Information Age: Escalation Dynamics in the Russo-Ukrainian War

Over the course of the now eight-month war in Ukraine, Russia has made vague and indirect threats of nuclear escalation. Those threats become more frequent and overt as Ukrainian counteroffensives gain momentum and the Russian military cedes territory. As President Biden stated on October 11, 2022 in response to some of these recent threats, the U.S. is now faced with the first credible threat of nuclear escalation in a generation. Unipolarity fostered an environment in which use of nuclear weapons rarely entered sober public discourse. In a way this is comforting—nuclear deterrence proved successful. On the other hand, much of the body of knowledge surrounding nuclear escalation is untested theory derived from Cold War-era assumptions. Analysis of the progression of the war in Ukraine suggests that legacy escalation theory, when reframed for geopolitical context and the modern character of warfare, remains relevant and can provide insights into the future direction of the conflict.

Escalation Theories and Metaphors

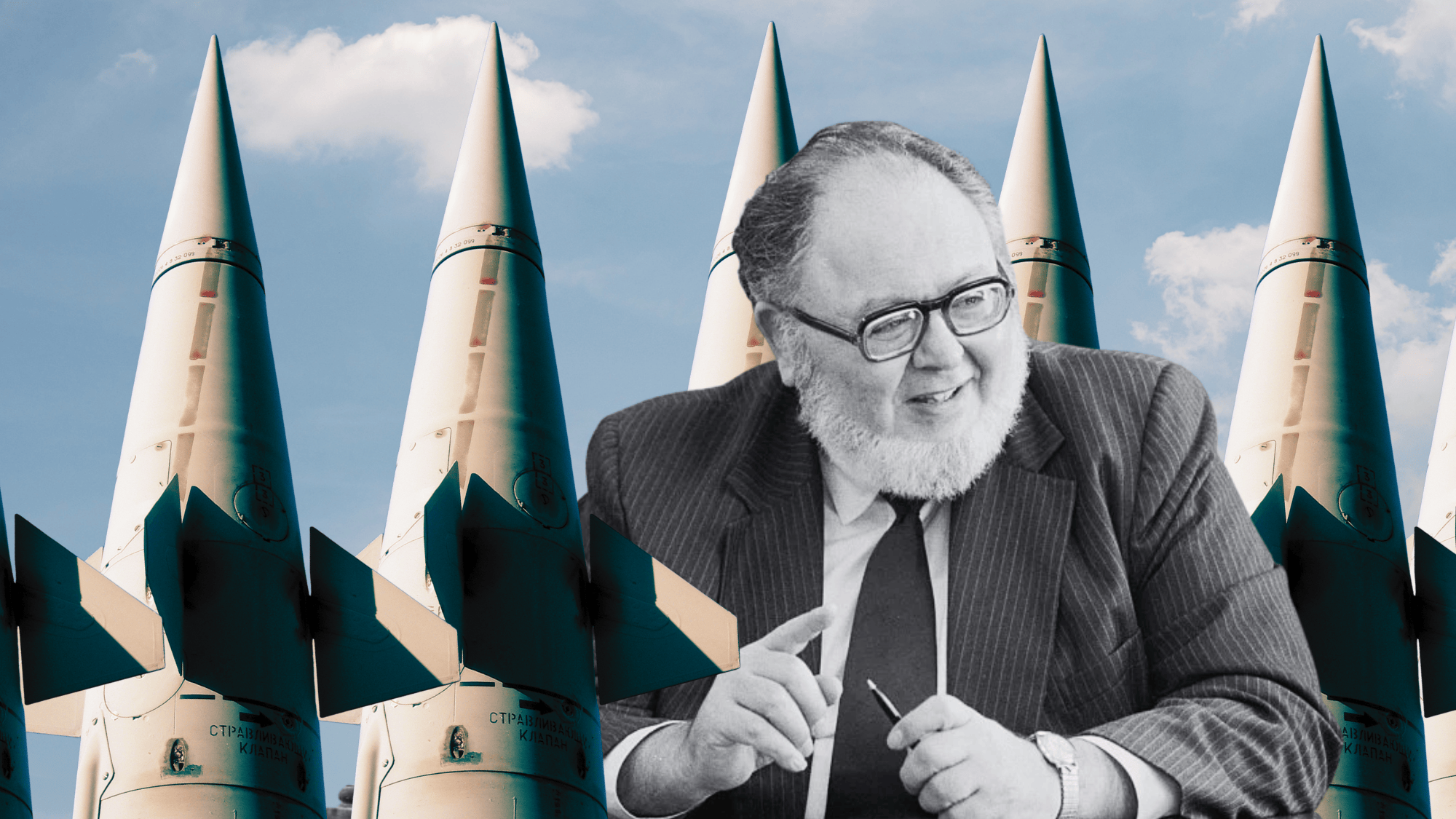

A useful theory of nuclear escalation should suggest how and under what conditions actors are likely to pursue more extreme means of coercive force. Nearly sixty years ago, Herman Kahn’s On Escalation proposed a simple and plausible framework for understanding escalation as a competition in risk taking, like a game of chicken. An actor escalates because it believes that the other side may find the risks associated with the escalation untenable and subsequently relent. Of course, the act of escalating carries the inherent risk that one’s opponent may be incentivized to raise the stakes and escalate further. Continued escalation is particularly likely when actors face existential threats—the risk of de-escalation is greater than that of escalation—or are at a disadvantage at the current level of conflict—the risk of maintaining the status quo is greater than escalation.

The core of Kahn’s theory is the “escalation ladder,” a graphic and narrative metaphor of iterative ways and means, progressing from interstate disagreement to nuclear Armageddon. His intent was to “facilitate the examination of the growth and retardation of crises.” Kahn was quick to point out that his escalation ladders were a tool to aid in understanding and contextualizing but should not be considered as a rigid template for every crisis. To that end, he identifies 44 “rungs” representing increasingly risky, provocative, and violent behavioral options, grouped into seven units. The work is an important glimpse at influential early-Cold War scholarship which has informed strategy and analysis for the better part of a century, and persists in influencing security discourse.

The persistence of Kahn’s 60-year-old theory raises important questions for scholars. Is this persistence a sign of superlative explanatory power or of analytical stagnation and untestable theses? How well can Cold War-era theory explain escalation behavior in the information age? Has the character of warfare evolved to an extent that undermines the theory’s assumptions of state decision calculus? The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine serves as a case study to examine whether modern great power escalatory behavior comports with Kahn’s framework.

The Road to War and Beyond

In many ways, the buildup to the invasion and first several months of the war followed an escalation progression that closely parallels Kahn’s ladder. The 2014 Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea, and persistent low-intensity conflict in the Donbas are important context. Putin’s subcrisis maneuvering progressed over years and commenced by establishing a crisis (rung 1) as grounds for conflict. These grounds were further laid by suggesting through political, economic, and diplomatic actions (rung 2), as well as rhetorical repetition that the crisis represented a threat to vital Russian interests (rung 3). The crisis progressed to what Kahn would call “traditional crisis” in January and February of 2022, as Russian threats became increasingly pointed and frequent (rung 4). Deliberate and systematic escalation manifested as Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s borders (rungs 5 and 6) and manufactured “dramatic military confrontations,” ostensibly to coerce Kyiv to accept terms (rung 9). The “harassing acts of violence” in the Donbass increased significantly, surrounding the recognition of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics on February 21 (rung 8).

The invasion, or “intense crisis,” began on February 24 with a flurry of escalatory activity, the penetration of Ukraine’s borders (rung 12) being only the most visible. Notably, diplomacy was maintained until the day of the invasion, when President Zelensky announced the severing of diplomatic ties (rung 10). Almost simultaneously, Ukraine announced general mobilization. Ukraine’s deferral of both moves until the invasion began suggests a desire by Kyiv to avoid escalation and deny Moscow a pretext for invasion. The “large conventional war” phase of the conflict persisted for months as initial Russian objectives proved unrealistic and the war became one of attrition. A form of compound escalation has flared up periodically in the form of Russian missile attacks against civilians far from the fight (rung 13). Finally, the annexation of Donetsk and Luhansk in early October 2022 represented a de facto declaration of limited conventional war (rung 14). Up to that point, Moscow scrupulously framed the war as a “special military operation.” Annexation of the territories reframes Russian military actions there as defensive. This—desperate and Orwellian as it may be—is significant in that Russia has committed to defending the breakaway republics just as it would its own homeland.

The Current State of the War

The present state of the conflict is one of conventional, attritional war punctuated with what Kahn would understand as references to “barely nuclear” war (rung 15) and “nuclear ultimatums” (rung 16). The Kremlin’s recent accusation that Ukraine is attempting to create a dirty bomb, despite being an obvious fabrication, creates a pretext for “barely nuclear” war. Kahn envisioned this sort of activity as an “accidental or unauthorized” use of nuclear weapons, but a false flag dirty bomb might just as easily serve the purpose. It would certainly be escalatory in a conventional sense and could potentially erode the nuclear taboo. Moscow’s vague and increasingly frequent references to using nuclear weapons serve to “shatter the illusion that ‘unthinkable’ means impossible,” to use Kahn’s description of nuclear ultimatums. On Escalation places little escalatory stock in threats that are “vague and heavily qualified,” yet Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling has garnered a tremendous amount of attention from the international community.

Going up?

That Putin would be willing to cut his losses at this point seems improbable. Likewise, the Ukrainian government insists that it will not negotiate or cease fighting until Ukraine’s territorial integrity, including Crimea, is restored. Many of Russia’s prior escalatory measures fell flat because they either failed to credibly convey a sufficient level of risk or because they underestimated Ukrainian risk tolerance. Assuming that Russia is not induced to the negotiating table and that Ukraine continues to retake its territory through grinding offensives, Putin has significant motivation to escalate the conflict. The conflict’s potential for further escalation is bound not by capability, but by Moscow’s appetite for risk as it relates to international response.

A Strong Ladder

The Russia-Ukraine case study suggests that Kahn’s escalation framework holds up when adapted to the unique characteristics of the conflict, as the author intended. While a handful of rungs were skipped over or occurred later than Kahn modeled, the ladder proved a relevant framework. Kahn explained that the unique dynamics of each conflict would result in deviations from his model, and exhorted analysts to adapt the ladder to fit relevant circumstances. In applying Kahn’s escalation ladder to the war, observers should note two important modifiers: the relative power dynamics between the competitors, and the character of the conflict of warfare generally.

First, the power dynamics between the competitors are critical context for understanding escalatory behavior in any given conflict. While Kahn had great power competition between nuclear-armed states in mind when crafting his escalation ladder, the current conflict is one in which Russia has a near monopoly on escalation. Russian behavior may be less constrained because the risk of Ukraine escalating to a higher rung is remote. The Russian risk calculus, therefore, is not based on credibility of further Ukrainian escalation, but on the risk of drawing third parties further into the conflict. Ukraine’s supporters, therefore, have a stake in ensuring that escalation is managed while supporting the objectives and autonomy of the Ukrainian people.

Second, Kahn’s ladder tracks surprising closely to the sequence of events in Ukraine which have, fortunately, been at the lower end of the risk continuum thus far. Kahn’s metaphor may likewise be useful in projecting credible paths to rungs higher on the ladder. As strategists and decisionmakers on all sides weigh how best to achieve their ends while managing risk, they would do well to consider how the structure of a modern escalation ladder reflects developments in warfare. As geopolitical norms and the character of war evolve, conceptions of escalation dynamics evolve in stride. New rungs emerge, old ones disappear, and the rungs assume new orders. Still, 60 years on, Kahn’s escalation ladder remains strong.

The image shows Herman Kahn (1922-1983), American futurist and Cold War strategist, who developed the “Escalation Ladder” theory. Views expressed are the author’s own and do not represent the views of GSSR, Georgetown University, or any other entity. Image Credit: PaleoFuture edited with Canva Images