A Dangerous Alliance: China, Venezuela, and the Twilight of Democracy in Latin America

In Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro has stolen yet another presidential election. After the general election on July 28th, the Democratic Unity Platform (PUD) opposition party published voting data from over 80 percent of the officially collected tally sheets. The tally sheets revealed that PUD candidate, Edmundo González, beat Maduro by a sweeping margin of over 35 percent. Maduro denounced these results as fraudulent and used the National Electoral Council (CNE), which he controls, to fabricate the claim that he had won 51 percent of the popular vote. After refusing to publish CNE tallies that defend his claim of victory, Maduro used violence to repress largely peaceful demonstrations against the official election results. This crackdown has seen 25 Venezuelans killed and over 2,400 arbitrarily detained, including more than 100 children.

The United States, and many of its allies and partners, recognized González, now in political exile in Spain, as Venezuela’s legitimate president-elect. After seven Latin American countries refused to accept the outcome of the election, Maduro cut off diplomatic ties with them. Among the few countries that extended their congratulations to Maduro was the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The PRC has consistently supported Maduro since his narrow election in 2013 and has remained an important diplomatic, economic, and political partner for Venezuela. As the Maduro regime leads Venezuela into diplomatic exile, the PRC will remain a decisive lifeline for Maduro to protect his position in power. As the PRC-Venezuela relationship strengthens, the United States’ policies must account for a Maduro regime that is increasingly protected by Beijing. Under the Trump Administration, the United States reignited a new ‘Monroe Doctrine’, which used harsh economic policies to pressure Latin American countries into aligning with Washington as opposed to rivals like the PRC. These policies did nothing but limit the United States’ leverage over authoritarian leaders like Maduro who had an alternative trading partner in the PRC. Maduro may become further emboldened as he does not need to rely on economic cooperation with the United States or other Western nations to maintain his power. With alternate streams of income from a nation uncritical of the Maduro government’s human rights records and policies, the human security situation in Venezuela will deteriorate further.

From Democracy to Dictatorship: The Chavez Legacy and Its Aftermath

Before 1998, Venezuela had been a vibrant democracy in Latin America. The democratic framework put forth in the 1958 Punto Fijo pact promoted power sharing among elites and led to decades of relative stability. In the late 20th century, discontent with the perceived failures of the Punto Fijo outcome paved the way for the election of Hugo Chavez in 1998. Although he ran on an anti-establishment platform with promises to empower the marginalized, Chavez’s administration orchestrated the erosion of Venezuela’s democratic norms, moving power from the people to his socialist regime. One of the key mechanisms the Chavez regime used to concentrate its power was its transformation of Venezuela’s national oil company, PDVSA.

Though Venezuela’s oil industry was nationalized in 1976, Chavez instituted policies that increased state control and aimed to explicitly link PDVSA with his regime. In 2003, Chavez’s ‘Hydrocarbon Laws’ shifted PDVSA’s focus from efficiency to political loyalty. These policies increased state control and limited foreign companies’ involvement in PDVSA oilfield ventures to ensure the Chavez regime retained the majority of profits. Chavez leveraged high oil prices in the early 2000s to funnel 10 percent of the PDVSA investment budget into his ambitious social programs. Chavez relied on his monopolization of Venezuelan oil to fund these programs which included healthcare initiatives and missions to tackle widespread poverty and illiteracy. In an attempt to bolster public support, overspending and overreliance on oil revenues for these programs atrophied the Venezuelan economy and increased inflation. In response to strikes and public discontent towards the economic crisis, Chavez fired 12,000 PDVSA employees and replaced them with loyalists to his regime.

The consequences of Chavez’s exploitation of PDVSA were inherited by his hand-picked successor, Nicolás Maduro. After the national oil industry collapsed in 2014, the regime went to great lengths to undermine democracy and consolidate its power. In 2017, Maduro replaced the democratically elected National Assembly with the new Constituent National Assembly (ANC). Maduro used the ANC to redraft the Venezuelan constitution and pack the government and courts with handpicked loyalists, leaving his power unchecked.

A Lifeline for Authoritarianism: China’s Strategic Embrace of Venezuela

Since the early days of the Chavez regime, the PRC has been an indispensable ally on which Venezuela’s authoritarian leaders rely for political, diplomatic, and economic support. The heart of this partnership is a no-strings-attached economic relationship. Chavez was keenly aware that a strategic economic partnership with China would help Venezuela to decouple itself from the United States and develop his Bolivarian socialist regime “as an alternative to the destructive and savage system of capitalism”. In 1999 and 2001, Chavez and his counterparts formed the China-Venezuela High-Level Joint Commission which advocated for enhancing political, commercial, and cultural ties between the two countries. Their economic partnership was cemented with the establishment of the China-Venezuela Joint Fund (FCCV) in 2007. The FCCV codified a loan-for-oil scheme in which Venezuela received loans from Chinese policy banks with parallel contracts in which PDVSA signed purchasing agreements with Chinese importers. Chavez saw the PRC as a more flexible alternative to Western lenders and their democracy-enforcing stipulations, mitigating his political risk as a loan recipient.

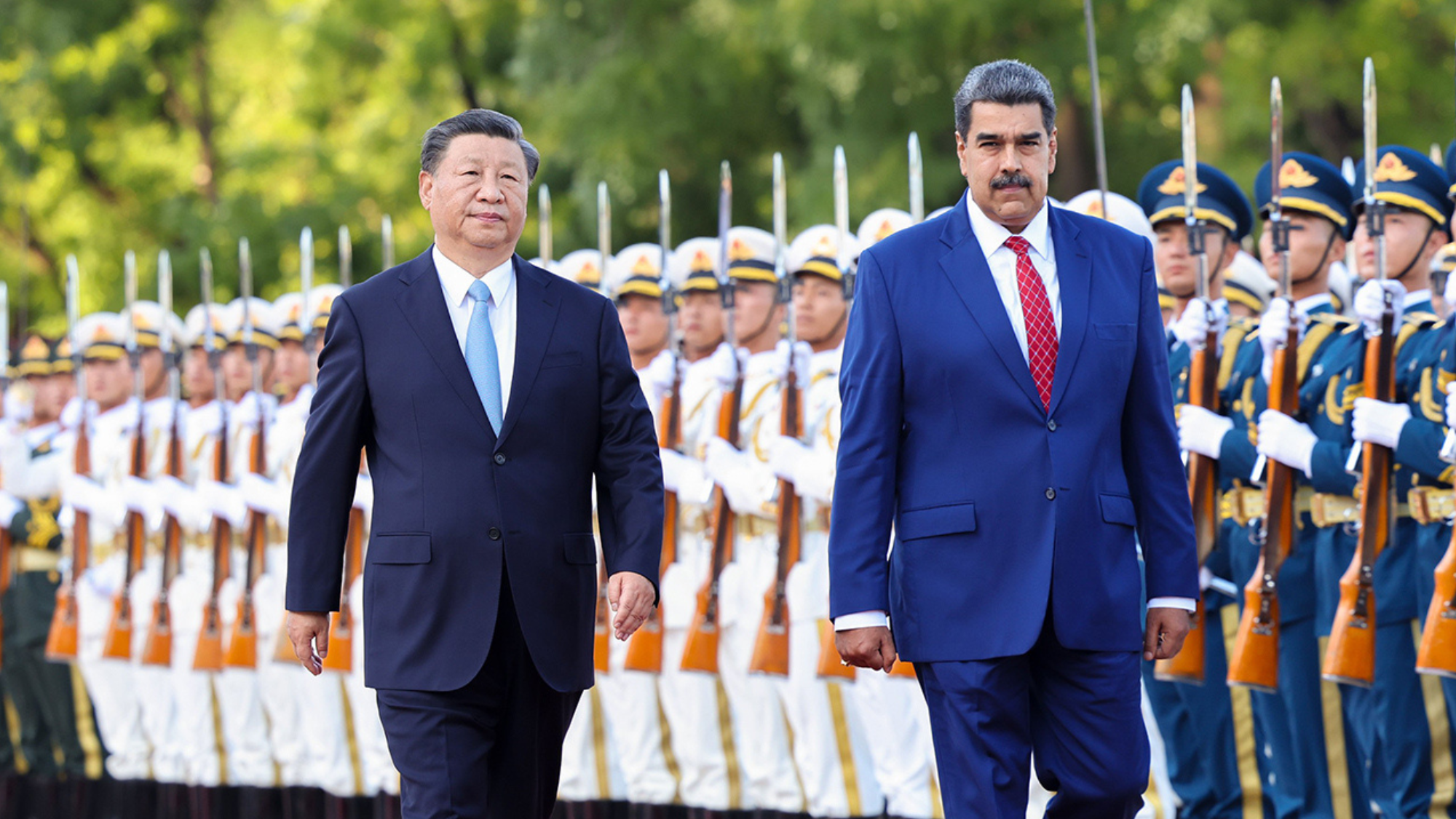

Venezuela’s reliance on its relationship with the PRC continued to grow stronger, with new infrastructure investments, joint ventures, and trade exchanges. By 2015, the PRC had loaned Venezuela more than $64 billion. After Maduro came into power, Xi Jinping, another newly appointed leader, carried on the PRC-Venezuela relationship with Chavez’s disputed successor. Xi quickly renewed the FCCV and upgraded the PRC-Venezuela partnership to a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’. After the collapse of the national oil industry in Venezuela, PRC lenders were cautious but maintained cooperation with Maduro and renegotiated bilateral debt to help relieve Caracas from US sanctions.

While Venezuela is indisputably the greatest beneficiary of their now ‘all-weather strategic partnership’, the PRC is not at a total loss. The PRC has long emphasized its desire to become an alternative development model for developing countries. By building strong relationships with countries in Latin America, the PRC is expanding its sphere of influence to the United States’ backyard. Although they extol a commitment to non-interference in internal affairs with their partners, by building bilateral relationships with authoritarian leaders like Maduro the PRC is setting an important precedent for non-democracies in Latin America. An economic partnership with the PRC and the security it provides may be seen as a winning formula for autocratic leaders who don’t want democratic regulators poking their noses into domestic politics.

Navigating the Waters: U.S. Policy Options in a Changing Landscape

While the PRC-Venezuela strategic partnership ascends, the United States’ relationship with Caracas continues to deteriorate. In 2017, the Trump Administration enacted an oil embargo against PDVSA which aimed to punish Caracas, force Maduro’s resignation, and restore democracy. These policies did little to dislodge Maduro’s repressive regime and exacerbated the economic and human rights issues facing the population. Harsh economic sanctions also allowed Maduro to paint the United States as the ‘real’ enemy of the Venezuelan people and stir popular support. According to the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), Venezuelans have higher trust in the Chinese government, which scored 51 out of 100 on a positivity scale, than the U.S. government, which scored 23.6. When asked what country should be a model for development, 27.9 percent more Venezuelans answered PRC than the United States.

Some policymakers criticize the Biden Administration for lifting the embargo on Venezuelan oil imports, the revenues of which go directly into Maduro’s pockets, and claim that renewed sanctions are needed to punish Maduro for the events of this year’s election. President-elect Donald Trump is expected to pick Florida Senator Marco Rubio, one of Washington’s most vocal critics of Maduro, as his Secretary of State. With Maduro still in power, it is likely that Senator Rubio will adopt some of the hardline sanctions like the 2017 oil embargo, which he played a key role in crafting. But, those same sanctions in 2017 did little to stop Maduro from committing election fraud in 2019. Maduro succumbing to the pressure of oil sanctions and stepping down seems unrealistic, especially given the safety net provided by the PRC-Venezuela partnership. Though the implausibility of regime change in Venezuela may be a hard pill for Washington lawmakers to swallow, they must continue to pursue viable policy alternatives.

To uphold a reputation as a stable partner in Latin America, the United States should use sanctions to target the Maduro regime directly and avoid exacerbating Venezuelans’ already dire humanitarian crisis. Sanctions targeted at individuals in the Maduro regime can limit the regime’s abuse of illegal earnings and erode Maduro’s credibility within his inner circle. Individual sanctions are also less likely to have public impact than broader United States sanctions on Venezuela’s industry, which 68% of the population already think have worsened their quality of life. In September, the US Treasury Department imposed targeted sanctions on 16 senior officials in the Maduro regime. These are a step in the right direction. The United Nations also recently diverted $3 billion worth of Venezuelan funds, previously frozen from sanctions, to finance health, education, food security, and electricity programs. The United States should play an active role in the negotiations to free up these funds and ensure multilateral organizations have jurisdiction to administer their initiatives which directly benefit the Venezuelan people. While the state of Venezuelan democracy may be disheartening, abandoning economic engagement altogether does little but open up a vacuum for the PRC to expand its influence, as we are seeing today. By pursuing moderate policies, the United States can continue to promote economic stability and maintain democratic influence in Venezuela.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not represent the views of GSSR, Georgetown University, or any other entity. Image Credit: Peoples Dispatch