Unveiling Masculinity: The Complexities of Gender Identities in Jihadi-Salafi Extremism

Judith Butler, a pioneer of third-wave feminist theories, described gender performativity as a phenomenon where “gender proves to be performance”— that is, gender identity is not an inherent or a biological phenomenon but is constructed through repeated and conscious actions (i.e., performances). In Jihadi-Salafi groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), group members perform gender through their strict adherence to traditional gender roles within group ideologies and operations. Tracing the manifestation of masculinity among Jihadi-Salafi groups—in both their ideologies and tactics— reveals that one of the ways to engage actors in de-radicalization is to address the harmful effects of rigid gender roles and the toxic hypermasculinity fostered within these extremist environments.

In this analysis, I leverage the term “masculinity” — meaning the socially constructed norms, behaviors, and expectations associated with being male, particularly within the framework of patriarchal systems — to highlight how the dominance, aggression, control, and perception of men as “warriors” are often valorized and reinforced within Jihadi-Salafi extremist groups. This notion goes beyond biological distinctions and explores how masculinity— a concept deeply entrenched in patriarchy — reinforces ideas of male exceptionalism to shape the behaviors and identities of men and women within (or targeted by) extremist communities. The lack of discussion on the LGBTQ+ community is not intended to diminish the importance of understanding diverse gender identities and expressions, nor deny their active victimization by these groups. However, the discussions in this analysis reflect the specific context of Jihadi-Salafi extremism, whose narratives primarily revolve around traditional, binary concepts of masculinity and femininity, which further demonstrates how Jihadi-Salafi groups both propagate and expect people to perform gender roles in narrow and inflexible ways.

Masculinity in Jihadi-Salafist Ideology

The core ideology of Jihadi-Salafi groups centers around a strict and puritanical interpretation of Sunni Islam and the Shari’a law, with the aim of establishing a Global Caliphate through armed struggle against perceived enemies of Islam, which these groups consider the ultimate form of jihad. Several key tenets of this ideology hinge on selective extremist narratives and often have toxic masculine undertones that incentivize members’ adherence to both the groups’ ideologies and their leaders’ orders. These groups’ propaganda romanticizes the idea of warriorhood and martyrdom for their male members and portrays individuals engaged in armed struggle as heroic figures fighting for a righteous cause. On the other hand, women members are often relegated to supportive roles focused on caregiving and nurturing, thus reinforcing patriarchal norms within these extremist circles.

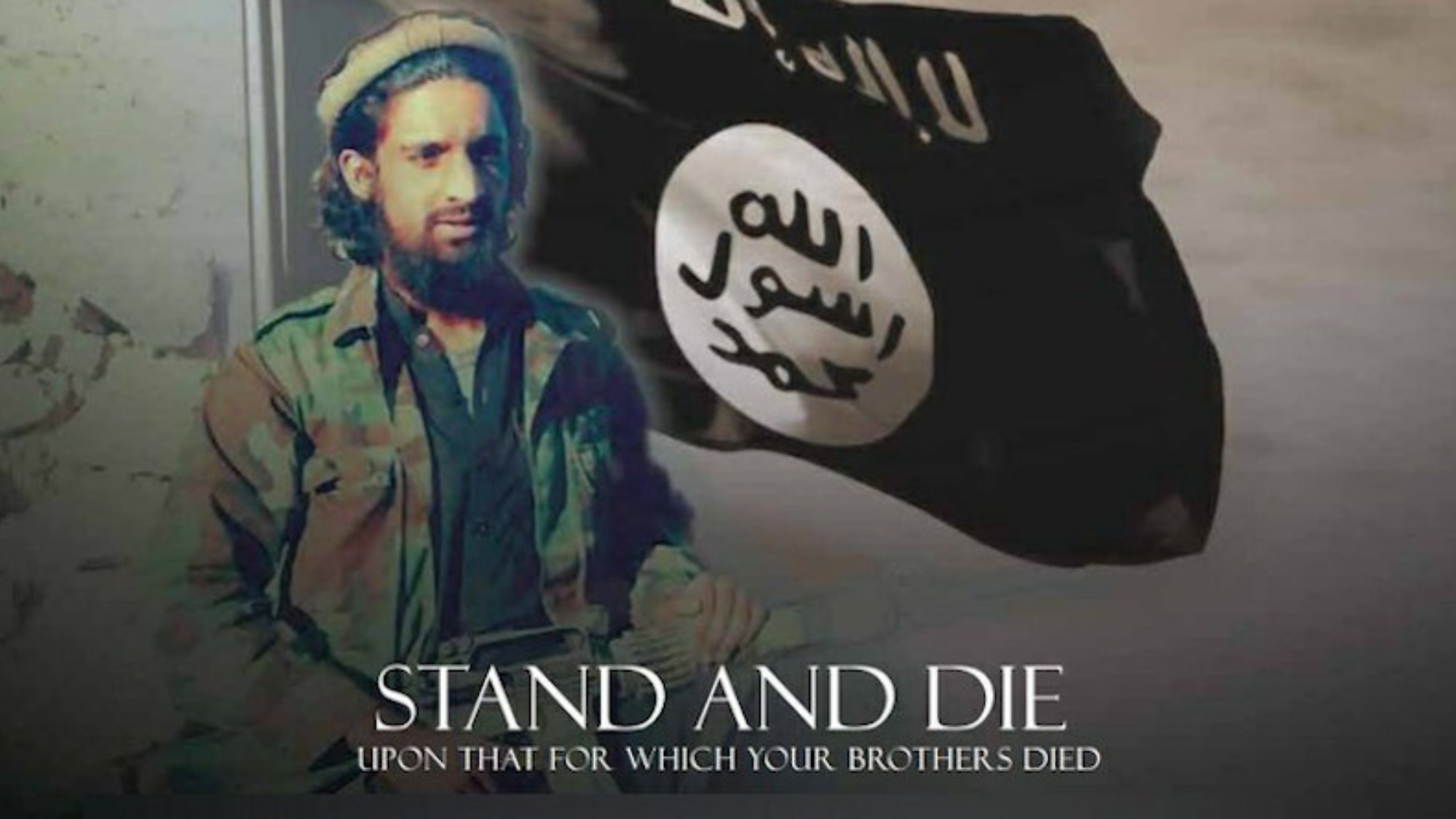

This gender rhetoric reinforces traditional gender roles that prioritize aggression and assertiveness in men while downplaying qualities like empathy, cooperation, and non-violence. By promoting these toxic masculine ideals, Jihadi-Salafi groups not only incentivize recruitment and adherence among their followers but also perpetuate a culture of violence and conflict. For instance, Jihadi-Salafi narratives glorify violence, aggression, and dominance as virtues essential for devout and honorable Muslim men, using terminology that exalts the idea of conquest and domination, framing it as a divine mandate to spread Islam and establish Islamic rule. They call upon men to embrace the “mujahid” status: brave warriors and defenders of Islam engaged in armed struggle, romanticizing the idea of sacrificing oneself in battle and eventually attaining martyrdom. For instance, propaganda materials depict male members as heroes clad in military gear, brandishing weapons in combat against their opponents. This imagery is designed to appeal to young men’s aspirations of strength, valor, and significance, encouraging them to join the ranks of the fighters.

Moreover, these groups often emphasize the concept of “ghazi” or warrior for Islam against infidels, drawing parallels to historical Muslim conquerors and warriors. Finally, it also creates a distorted perception of strength and honor, which contributes to further radicalization by fostering an environment where violence is normalized and even celebrated. As members continue to perform this gendered narrative, they may become increasingly desensitized to the human cost of their actions and view violence and domination as legitimate means to achieve their goals.

Jihadi-Salafi groups assign distinct and traditional gender roles to men and women based on extremist interpretations of the Quran, the Hadiths, and the Shari’a law. The perpetuation of such gendered narratives leads to the creation of a chauvinistic collective Jihadi identity, where aggression, violence, and dominance are not only celebrated but also deemed essential to being a devout Muslim man. Masculinity is associated with leadership, protection, and warfare, and men are expected to perform this type of masculinity by engaging in armed confrontations, military operations, and strategic planning to establish and maintain the Caliphate. Outside of conflict, men are often portrayed as the providers and protectors of their families and communities, tasked with upholding religious and moral values.

On the other hand, women are assigned roles that revolve around domesticity, support, sexual purity, and reproduction. They are idealized as caretakers, responsible for nurturing and raising the next generation of believers. Women are expected to provide moral support to their husbands and male relatives, engage in household duties, and play a supportive role in the overall functioning of the Caliphate. This involves child-rearing and actively advancing propaganda campaigns to both glorify the group and aid in recruitment. In Jihadi-Salafi ideologies, women enjoy little agency and are expected to strictly adhere to behaviors and norms dictated by men. For instance, one former Al-Qaeda “foreign fighter” I interacted with on the condition of anonymity revealed that his time in Al-Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan involved little to no interaction of the fighters with women, and he could not speak to the treatment of women within the camps since they were largely not permitted to leave their homes.

The “Crisis of Manhood” and the Role of Women

In addition to their prescribed gender norms, Jihadi-Salafi groups often call upon a “crisis of manhood” to frame their grievances, inform ideology, and recruit new members. Jihadi-Salafists define this “crisis” as the erosion of Islamic values due to perceived Western influences and secularism. They argue that Western ideas and secularism emasculate Muslim men and thus deprive them of their honor, strength, and devotion to Islam. To combat this crisis, Jihadi-Salafi groups call upon men to reclaim their masculinity through violent and assertive actions. This narrative glorifies violence and dominance while mocking and decrying signs of personal vulnerability. Groups such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS use this gendered narrative to target young men’s desire for recognition and belonging. Recruiters deliberately and openly challenge their masculinity and shame them into committing violence as a way to “prove” their masculinity through violent performance. For example, ISIS and Al-Qaeda propaganda often strategically features women and children—who are either themselves portrayed as “fighters” or as “victims” in need of protection— to suggest widespread social failure and, subsequently, suggesting the real or metaphorical emasculation of the men who were expected to defend them.

Similarly, ISIS’s use of child soldiers in videos plays on the discomfort many men feel at the thought of a child being more empowered than themselves to avenge perceived humiliation. Women also reinforce the idea that being “mothers, wives, or widows” of the fighters is an honorable position. Their statements extol the “martyrdom” of their loved ones and further amplify societal expectations for men to be self-sacrificing warriors.

At an operational level, Jihadi-Salafi groups reinforce militarized masculinities. Dier and Baldwin describe militarized masculinities as linking military service and the “idealized warrior” with manliness, thus legitimizing military power and force. In other words, by reproducing militarized masculinity, Jihadi-Salafi groups legitimize their violent methods and offer “martyrdom” status to men who participate in them. For example, participating in suicide bombing is often portrayed as the ultimate sacrifice and sign of courage and reinforces the narrative of violent resistance as a “masculine” virtue. Similarly, unconventional warfare tactics — such as ambushes, assassinations, and guerrilla warfare — are framed as strategic and cunning tactics emblematic of skilled and resourceful warriors. These views come from interpretations of historical Islamic warfare, particularly during early Islamic conquests, that showcase strategic tactics and flexibility in combat. For instance, the different ghazwa— raids or expeditions personally undertaken by the Prophet Muhammad and his companions— often involved guerrilla-like tactics that were strategic and aimed at weakening enemy forces.

Contrarily, women in Jihadi-Salafi groups are typically relegated to supportive roles, such as providing moral support or logistical assistance, though some also engage in public-facing roles, such as policing and propaganda. However, while women’s groups such as the Khansaa brigade—an armed ISIS women’s battalion and morality police—perform activities traditionally associated with “masculine” roles like carrying and using weapons, they still operate within traditional gender norms that underscore women’s subservience to men. Notably, their jurisdiction is limited to other women, and their combat and operational roles are designated to them by their (almost always male) superiors. Even following the disintegration of the ISIS “Caliphate” in Iraq and Syria, the Khansaa brigade’s responsibilities persist in the Al-Hawl refugee camp, where they continued to enforce ISIS’s strict dress codes and standards of behavior for women. In other words, ISIS selected a small number of women to use their gender to further reinforce traditional gender roles on other women and ensure the segregation of genders within their organization.

Breaking Free From Stereotypes: A Way Forward

Addressing how extremists understand and perform gender in our analyses — especially through the lens of patriarchal values — is crucial to combating violent extremism. Firstly, challenging patriarchal structures in Jihadi-Salafist gender ideology can disrupt gendered recruitment messages. Rigid gender roles that promote toxic masculinity, glorify violence, and limit opportunities for women create a fertile ground for extremist recruitment. By challenging these structures through promoting gender equality, we dismantle the narrative that links masculinity to aggression and dominance and thereby undermine extremists’ reach to people who resonate with their gendered messaging.

Secondly, directly identifying and addressing how the patriarchy restricts women’s agency and participation in society can help formulate counter-extremism messaging directed at women. Exposing and analyzing the patriarchal and male exceptionalist underpinnings of Jihadi-Salafist gender ideology can challenge extremists’ false promises of “women’s empowerment” within narrow parameters. Empowering women and promoting their active involvement in countering extremism can both disrupt these narratives and provide alternative pathways for women to engage in meaningful social change.

Finally, addressing the patriarchal roots of Jihadi-Salafi ideology—and many other extremist ideologies at large— also challenges the broader society’s patriarchal beliefs. By demonstrating ways that patriarchal gender norms fuel extremist ideologies, recruitment, and operations, we can foster a more inclusive and gender-equal society that is resilient to extremist narratives, especially those that seek to undermine women’s rights and align male empowerment with cruelty and violence.

Acknowledging gender as a socially reproduced construct is crucial because it contextualizes how extremists construct, perform, and exploit gender norms to advance violent and hateful ideas. Critically analyzing gender roles and performance in extremist contexts, such as Jihadi-Salafi organizations, thus lends greater insight into how extremists conduct operations, recruitment, and identity formation.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not represent the views of GSSR, Georgetown University, or any other entity. Image Credit: Islamic State propaganda published in its “Ghazwa-e-Hind” magazine via EurasiaView